Korea is Everywhere, What am I?

Locating the self amidst the rise of South Korea's cultural power

Hi. This is an essay I wrote about the soft power of Korea, and my relationship to the country and its culture. I hope you’re all staying warm. ☆

I grew up associating 32nd street not with Penn Station nor the Empire State Building, but a portal to the block-long strip that made up New York’s Koreatown. My family and I had our favorite restaurants: BCD for hot red soondubu, Gammeok for milky seoullangtang, and Han Bat for oily, chewy jajangmyeon. After our meal, we’d pick up a loaf of milk bread from Paris Baguette and groceries from H Mart, then take the train back uptown.

It used to bother me that Chinatown sprawled across an entire neighborhood at the tip of Manhattan, while us Koreans were sequestered a to a little block (in Midtown, no less). But I also liked that it was small and (somewhat) secret. It was the only place in the city I could be surrounded by Korean faces and hear murmurs of a familiar yet incomprehensible language. But Koreatown is no longer under wraps—it’s exploding.

Last year, I listened to a podcast about the rising popularity of Korean culture around the world. In 2008, South Korea’s Ministry for Food began a government-sponsored campaign to take Korean cuisine international, by increasing the number of Korean restaurants abroad and standardizing words like kimchi and galbi so English menus would all have the same spelling. Why food, of all choices?Ligaya Mishan writes in the New York Times:

“The American sociologist Michaela DeSoucey has framed gastronationalism as a response to globalization and the erasure of difference, a ‘form of claims making,’ enshrining dishes and ingredients as cultural patrimony akin to art or literature, the material turned symbolic, more fundamental than borders on a map to a people’s sense of who they are.”

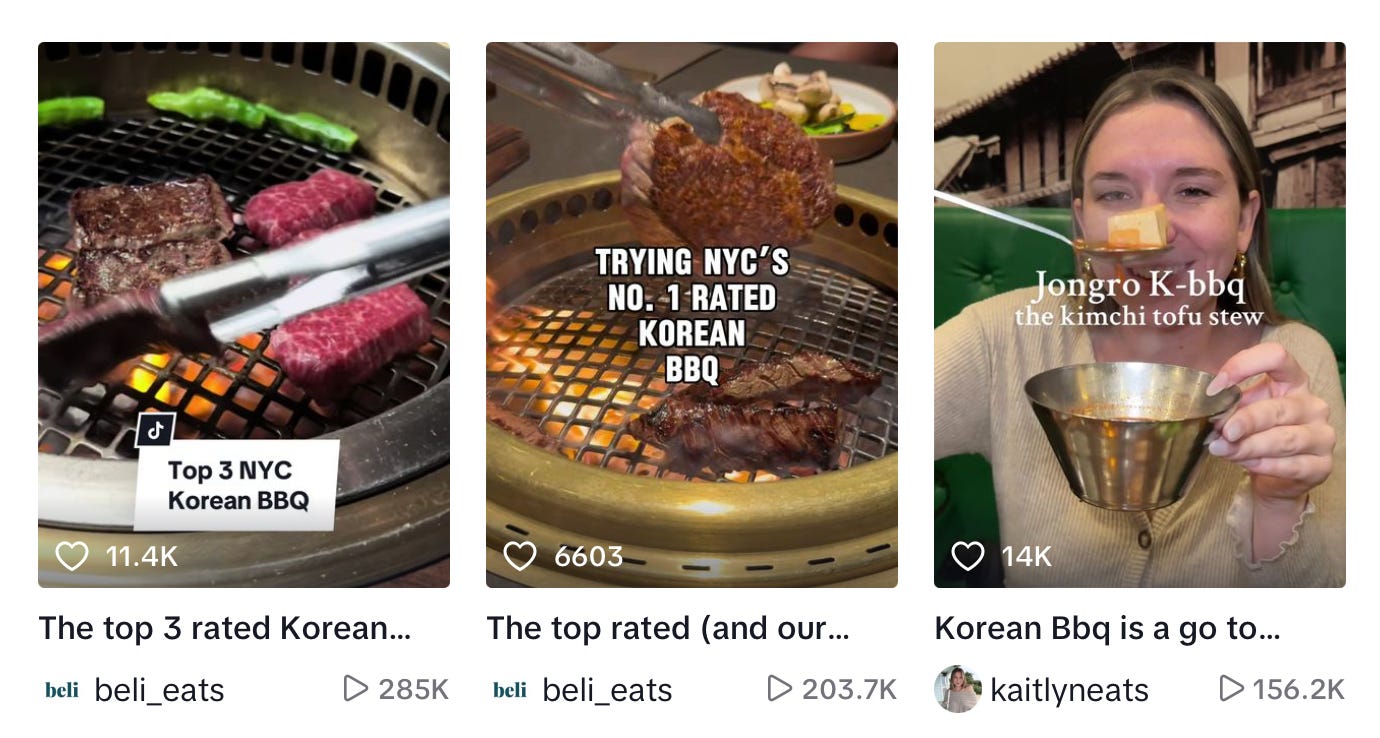

South Korea’s “gastrodiplomacy” worked—less than a decade later, there are Korean restaurants everywhere, even down my street in New Haven. American grocers sell cabbage and radish kimchi in their refrigerated sections. Former New York Times food critic Pete Wells wrote about how Korean establishments like Jua and Atomix are replacing French cuisine as the standard for fine dining in New York City. None of them are on the K-town strip.

I haven’t tried any of the multi-course tasting menus, but I have gone to some modern, upscale Korean restaurants that have begun to pop up around the city. Many of them come from Hand Hospitality group, who churns out Asian eateries at an eye-widening cadence. I like their food—it’s salty, sweet, spicy, satisfying—but they lack the unpretentious charm that makes places like Gammeok so special. In the veteran restaurants, you recognize the same faces every year and the food tastes like old ladies made it with their hands, so familiar with the flavors they could endlessly recreate them based on touch. There are no TikTokers recording with ring lights, and the banchan is unlimited and free-flowing.

After Japanese occupation and the Korean War, South Korea sought to revitalize its economy and international reputation. Since it’s such a small country, it must wield “soft power,” the intangible kind that amasses control through images instead of force. Hallyu, or the “Korean Wave,” is the term used to describe the growing influence Korean culture has on the rest of the world. Food is only one part of it—hallyu encapsulates film, television, fashion, beauty, music, art, design and innovation.

Hallyu 1.0 began with the export of television and cinema to Chinese-speaking countries. In 1995, the National Assembly passed a law that provided tax incentives for film production in an effort to revive the Korean film industry after a period of strict censorship under Park Chung Hee’s military dictatorship.

Hallyu 2.0 took over in 2008, the same year that the Korean government began their gastronomical campaign. It’s marked by the spread of Korean culture through the internet and the transition to K-pop as the country’s primary cultural export.

The Korean Wave is all about exporting culture to new places. But what if you’re on the receiving end? Where does all of this leave Korean Americans who are witnessing their first culture explode within their second?

I saw Crazy Rich Asians in Hong Kong when it was released in 2018, and I teared up at the wedding scene because of how stunning it was—not only the water streaming down the flower-studded aisle, but the unabashed depiction of Asian beauty, decadence, and celebration. A year later, I saw Parasite with my family back in New York, and I was floored.

At the time, representation still felt new, and I was strangely emotional about seeing Asian actors on the same screens I grew up watching blockbusters on. Then there was Squid Game, Minari, The Farewell, Beef, Past Lives, Everything Everywhere All At Once, To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, Didi. They weren’t K-dramas or just Koreans cast in Hollywood films, but a third category that felt deeply personal. It was weird for these movies and shows to be a part of general pop culture discourse. I was offended when someone criticized them. I told myself that they just didn’t understand, or else they also would have cried in the theater at the restrained and aching depictions of love. Or they were so used to seeing themselves reflected back to them that they didn’t know what it was like to experience it for the first time.

My relationship to Korea (the actual country) is complicated. I’m not fluent in the language. The family members that tether me to certain neighborhoods and homes are too old or far-removed. The Korean Wave exists partially to promote tourism—in 2023, South Korea was the 14th most visited country in the world—but when I go, it isn’t a vacation nor a homecoming. Instead, it feels like I am remembering a place I have forgotten, the memories of my ancestors like a flood over my body.

I was last in Korea with my family in December 2023. We spent most of our time eating meals with relatives, where I observed conversations: they would speak in Korean, and my mother would respond in English. On one free day, I found a neighborhood called Seongsu-dong that was supposed to have good vintage. We drove away from the historic district onto a main drag that resembled Brooklyn. The secondhand shops were stocked with Acne Studios and Vivienne Westwood. There was an Aesop and a Byredo next to each other, just like in Williamsburg. The two cultures I grew up between had become so enmeshed that inside the stores, only small details like the currency on the price tags would give away which city I was in.

It’s a funny feeling to watch your culture become trendy. I’ve never been a big fan of K-pop, but I watched BTS perform at the Jingle Ball and Jennie from BLACKPINK act in HBO’s The Idol. My friends have as many Korean skincare items on their bathroom shelves as I do. Sephora has a page for K-beauty on their website. It feels like everyone is traveling to Seoul to get their color analysis and facial treatments.

Girls in middle school used to come over to my house and ask me if fishcake was safe to eat and why I was eating soup for breakfast. They’d wince when I opened my fridge and it smelled like punchy, sour kimchi. Now people are paying $500 a piece to eat the same flavors in smaller portions and elevated, tweezer-required preparations. The racist joke of pulling your eyes back has somehow mutated into girls getting surgery to make it permanent.

My life has changed too, in small ways. I took a class last semester on modern Korean literature (in all of high school, we never read a book by an Asian author). My friends are excited about cooking and eating Korean food. The Korean creators I love are starting companies and opening restaurants. Men give me more attention—my Asian friends are less worried about lacking desirability than the creepiness of fetishization. I had three friends text me about martial law in South Korea before I had even woken up.

The more visible Korean culture becomes in the mainstream, the easier it gets to feel proud representing it. But I can’t shake the feeling that like any fad, the Korean wave will recede, and I might disappear with it. I know this isn’t true, and I don’t need BTS or dry-aged, gold-dusted barbecue meat to prove that I exist. Maybe I’ll go back to 32nd street, the old version, when the crowds die down, and get steaming bowls of soup for as long as I am in New York.

Happy Holidays.

This resonates so heavily with me because as a Korean American woman in her 30s I often had a hard time articulating the lonely feeling of people loving your cultural food and items and art but somehow almost objectifying me. & also sometimes I feel reduced to an aesthetic or people often perceive or assume I must be a certain way or like certain things because I am Korean. ♥️

People often forget that what we easily deify and put on a pedestal comes with a lot of chaos. & I am happy people are enjoying some of our cultural items and customs ♥️ that part is also nice to see. It’s a back and forth dance.

so good and so real. it’s crazy to think about how much of the attitudes around korea has changed in so little time.