For my last assignment of Daily Themes, we were tasked with writing answers to infraordinary (opposite of extraordinary) questions—why do we do what we do? Why don’t we ever wonder?

I don’t know how often people say I love you without meaning it…but I wrote a fictional story to ruminate on it. I also drew little illustrations. I hope you enjoy.

I. Last night I met a girl who grew up with my best friend Sarah. She was visiting New York for a week, staying in Sarah’s apartment on her blue velvet couch. Her face looked like an actress’ I had once seen in a Broadway show but then forgotten. Actually, she didn’t look like that particular actress. She looked like a room full of casting calls.

Her name was Diana. Before Sarah had the chance to introduce us, she lunged forward and wrapped her arms around me. I’m so happy I finally get to meet you, she said. I feel like you’re the other half of Sarah’s brain. I hugged her back, delicately tapping my fingers against her back, and agreed. It was about time, and here we were, on an orange-tinted street corner in the middle of June.

The three of us sat down for dinner at a new-age bistro, where the dinner plates and movie posters and mustached waiters were imported from France. We shared steak frites and a three-egg omelet and escargot bathing in green butter. For dessert, we dipped cold spoons into profiteroles with cream and candied hazelnuts. The conversation was a little stale—we discussed boyfriends, bosses, exercise regimens. It felt emblematic of our eventual, inescapable demise into middle age, when we’ll be so removed from the world the only thing left to talk about is ourselves.

I hailed a taxi outside of the restaurant. I lived all the way uptown, near Riverside Park. I hugged Sarah and told her I’d see her soon. I hugged Diana and reiterated how nice it was to meet her. As she pulled away, she told me she loved me. Casually, airily, without a second thought. There was a flash of lighting. Rain, in the middle of the summer.

II. The first time Sarah said I love you, she didn’t mean to. She met Oliver at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they hosted late nights on Fridays for couples to stroll the galleries and brush shoulders and drink cups of chamomile tea in the Egyptian room. It had been Oliver’s idea, but he didn’t know that Sarah had spent her childhood visiting The Met. Her mother’s first job out of college was giving tours of the American wing. Sarah used to go on Saturdays, early, before the crowds, and look up (everything was so tall back then) at the war paintings, the marbled goddesses, the silver armor. There was a restaurant on the fourth floor that served kids meals in taxi-shaped boxes. She plucked her chicken tenders and fries out of the roof of a cardboard yellow cab.

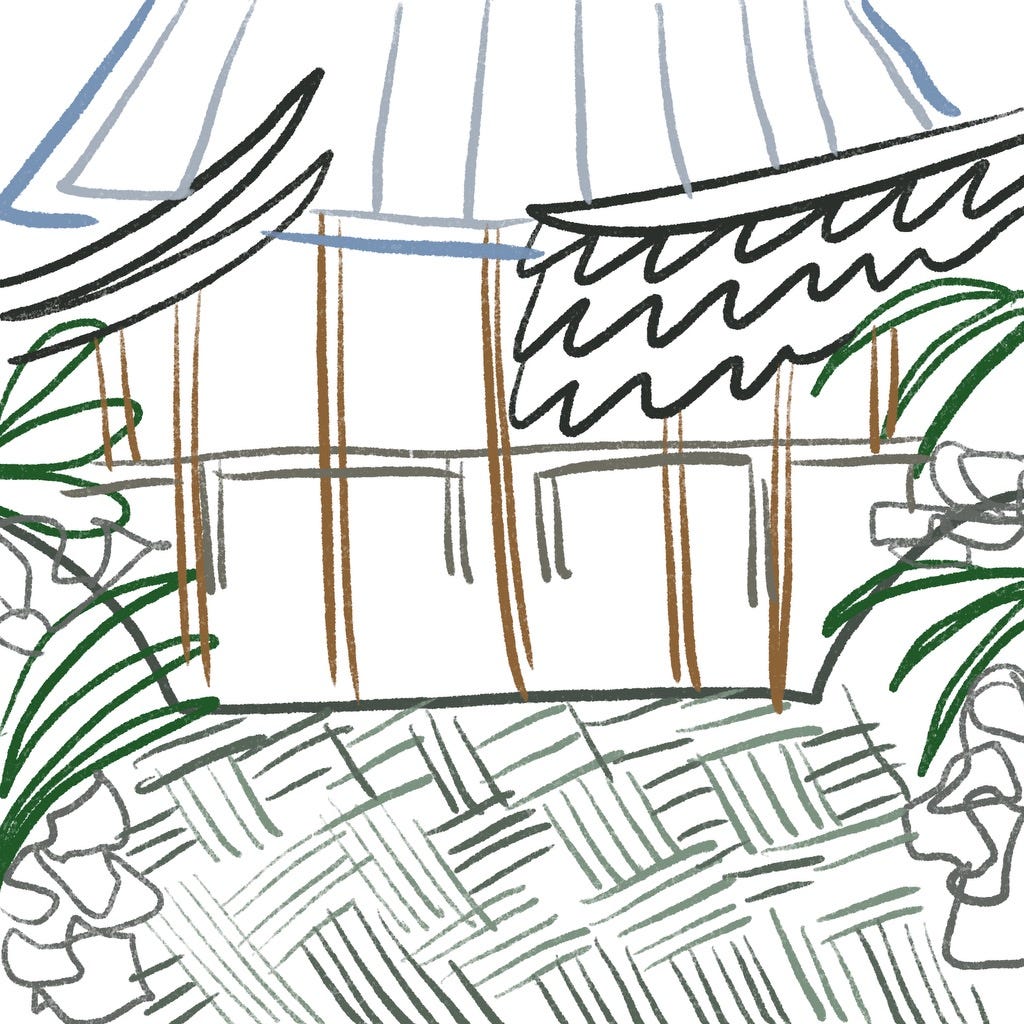

Sarah took Oliver to her favorite room—the 17th century Chinese garden. She loved the long-leaved greenery growing from the rocks, the ceramic tiles arranged like Jenga pieces on the floor, the reddish wood, and the paneled skylights that almost made her feel like she was outside. The best parts of the museum were its reconstructions—Sarah used to walk through the grand Parisian salons and the low-ceilinged Wentworth house and imagine herself living there.

Oliver did his best to keep up with her. He was a computer scientist. He didn’t have much to say about form or technique, but he was proud of his ability to feel genuinely enthusiastic about the things other people liked. He asked her questions and listened when she spoke.

They stayed at The Met until the security guard gently reminded them that the museum was closing in ten minutes. Oliver retrieved both of their jackets from the coat check. He held Sarah’s up and helped her arms through the sleeves. At the 84th street exit, he wished her good night. Good night, she replied, as she was walking downtown. And then, like a reflex: Love you.

Sarah called him when she got out of the Subway on West 4th to tell him it was a terrible accident.

III. Diana’s parents never told her they loved her. It wasn’t a part of their vocabulary. Instead, her mother cut fruit in her palm, quartering sweet strawberries and slicing Korean pears without having to look down at her hands. She would arrange them inside shallow ceramic bowls and place them on the kitchen counter, or if Diana was lucky, she would deliver them to her bedroom. In April, Diana’s father filed her taxes. He told her which index funds to invest in and which bike helmet to buy. He read over her freelance contracts before she signed them. He moved her into her first apartment, a six-floor walk up in the Lower East Side. When she was in college, Diana’s parents called her every Sunday, at 1pm on the dot, after they came home from church. They asked about her classes and her job search and whether or not she had found a boyfriend. They never said I love you, but she knew.

At first, she was surprised by how easy it felt. She repeated the words back to men who expressed affection for her, even if she didn’t care much for them. I love you too was easier than the alternative—silence, resentment. Diana wasn’t a mean person. She didn’t want anyone to feel bad. She learned, actually, that saying I love you made people feel very good. So she started saying it to her best friends, her acquaintances, cashiers at the grocery store after they bagged her produce, baristas, dogs on leashes, strangers at parties. She felt lighter every time the words left her mouth.

IV. Just after they started dating, I ran into Sarah and Oliver at the Union Square subway station. It was the first pleasant Saturday morning of spring. I saw Sarah first, with her dirty-blonde curls and pleated pink-and-green striped pants she had been wearing since our freshman year of college. When she walked, she swayed back and forth, as if she were accommodating a hidden tide. It made her instantly recognizable.

They were both excited to see me, or at least pretended to be. We learned we were both going to the farmers market that ran through the park’s main artery. The three of us inspected the stone fruit and sampled the wildflower honey and made small talk about the weather, the traffic, the smell of the city. I couldn’t decide whether it was awkward because I was there, or if I was catching them in an off-moment.

When Oliver left to find a bathroom, Sarah nudged me. He told me he loved me last night, she confessed. And I didn’t know what to do. I mean, it’s only been a couple of weeks. I accidentally said ‘Love you!’ after our first date at The Met, but I profusely apologized afterward. She was shaking a little bit, her eyes wide and glassy. I couldn’t think of anything to say. I kind of laughed. Then he looked all freaked out, and told me he was kidding.

V. Diana found Sarah’s friend from college very cold. At their dinner, she responded to all of her questions in no more than two sentences—either she only wanted to tread on the surface, or she had forgotten all the details of her life. Diana had broken through the hard shells of a lot of reserved people, usually by deciding to be their friend and pestering them until they warmed up and the scales evened out. This girl was different. At the table, she picked at the skin around her nails and kept turning her head toward the street, scanning the faces and pigeons and passing cars. Her cheeks reddened when she had her first sip of wine, tiny little dots specked across her cheeks.

Still, Diana couldn’t help but try. She meant every I love you she said, because she didn’t think I love you was necessarily romantic. Love didn’t have to be deep and burdensome and sentimental and persistent. It could be breezy, joyous, affirming, welcoming, temporary. It could be self-multiplying, infinite. She was calling out to the world and waiting for it to reach back.

I LOVE YOU!!! See you next week.

wonderful!!

Terrific Arden as always !!! I LOVE U!